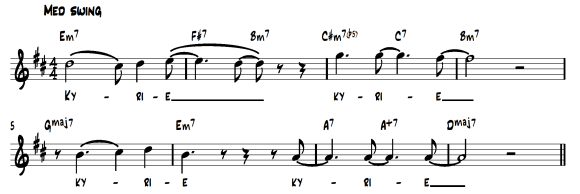

As a sequel to extroversive semiosis, we have introversive semiosis (if you have not read the previous post, I invite you to do so). This was Kofi Agawu’s definition: “[i]ntroversive semiosis denotes internal, intramusical reference, both backward and forward, retrospective and prospective” (Agawu 1991, 132). If extroversive semiosis inhabits the space dimension – where meaning is brought about by referring to objects outside the realms of the piece – then introversive semiosis is a linear method that inhabits the time dimension for its reliance on material that has been or will be heard. For example, the ‘Christ’ theme in my composition (which is a musical cryptogram, a topic for another day) is first heard as a melody in the brass at the word ‘Christe’ in the Kyrie movement:

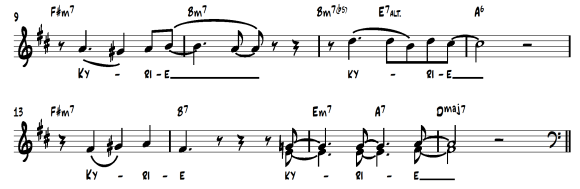

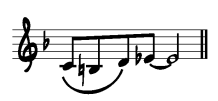

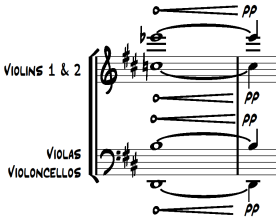

However, it is heard harmonically in the strings at the first bar of the Kyrie:

The strings’ prospective reference to the ‘Christ’ theme was bound by the time dimension of the piece; it was an intramusical reflection and distortion. The reason for this introversive technique was to convey the theological belief that Christ was at the beginning of the creation of the universe.

Introversive semiosis could be used in many other ways, and it has. Any point in a piece that involves the development of any thematic material (melodic, harmonic, structural, etc.) signifies the original theme. However, this is also where the definitions of extroversive and introversive semiosis converge. If a theme is being developed (introversive) so to signify an object outside the piece (extroversive), then the distinctions blur. An example would again be the strings’ prospective implication of the ‘Christ’ theme: the intramusical signified object is the ‘Christ’ theme – later used – in the brass, the extramusical signified object is the doctrine of Christ’s pre-existence (John 1:1-18). Therefore, the strings use both extroversive and introversive semiosis in the same instance.

While this ambiguity might seem to be a reason not to need such binary terms as ‘introversive’ and ‘extroversive’, they still signify the relationship between perceived objectivity/ autonomy and subjectivity in music. When one says a semiotic element is referring to outside the piece, they mean that they interpret there to be a certain reference outside the piece. Evidently, subjectivity is a strong influence in extramusical signification. On the other hand, it is easier to find a reference that stays within the limits of the piece because of our brains’ abilities to recognise patterns. Of course, this does not mean that this process is truly objective or autonomous, though it is also not as dependent on our interpretation of the semiosis than extramusical reference itself. Therefore, the terms are helpful to understand the concepts, though they must be used with caution; this is so one does not inadvertently polarise the distinctions more than they already are polarised.

As was said earlier, I will soon be discussing musical cryptograms, musico-semantic association, and their connections with introversive and extroversive semiosis in my composition and research.

Bibliography

Agawu, Kofi. 1991. Playing with Signs: A Semiotic Interpretation of Classic Music. Princeton: Princeton University Press.